I was in the US last week visiting gardens in two states. It was exciting to be in a different country talking to gardeners and designers over there, and documenting two very different gardens designed by Dan Pearson and Luciano Giubbilei for House & Garden, with photographer Andrew Montgomery. It was interesting to see how these British designers are bringing the trend for a more nature-led aesthetic over the Atlantic. There are plenty of ‘English gardens’ with box hedging and roses in the eastern states of America, but the native plants over here are pretty exciting - echinaceas, heleniums, rudbeckias, asters and many more that we grow as garden plants over here - and more designers are using them to embrace the movement towards a more biodiverse and relaxed style of gardening.

The first garden we visited was near Charlottesville in Virginia, a collaboration between London-based Luciano Giubbilei and American plantsman Roy Diblik. Set out on a slight slope with the Blue Ridge mountains as the backdrop, the garden was simple in concept with curving, amorphous beds filled with emphatic drifts of perennials and grasses. It’s a survival of the fittest garden, the planting designed to adapt to the environment with minimal (or no) irrigation. This inevitably means a certain degree of trial and error, so you need clients broad-minded enough to accept that some plants will need to be replaced.

At this time of year the plants are starting to fade gracefully, seed heads and tawny grasses mixing with late season flowers, reflecting what is going on in the landscape. The whole point of this garden was not to detract from the spectacular views; anything formal or terraced would have looked completely out of kilter. As it is, the eye wanders seamlessly from the soft curves and hummocks of the planting to the rolling fields and woodland beyond, with the mountain ridge on the horizon (which really is blue as the sun goes down).

At least three quarters of the plants in the planting scheme are native to north America, so not only do they feel and look right in the landscape, they are better for wildlife and generally need less water as they are adapted to local conditions. At this time of year, the stand out plants were the aster Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘October Skies’, with neat mounds of starry blue flowers, Amsonia hubrichtii, whose ferny foliage turns a rich yellow or ochre in autumn, and the goldenrod Solidago caesia, which grows in the wild in upland woodland clearings in the northeastern states. Various different grasses brought different muted colours and textures to the scheme, from the hazy gauze of Eragrostis trichodes to the more defined biscuit-coloured fronds of Panicum virgatum ‘Heavy Metal’.

After an early morning and an evening photographing this garden, we got back on a plane and flew from Washington to Hartford, Connecticut, into what felt like a different season. Autumn was more advanced here with the trees turning the classic reds, russets and ochres of a true American Fall. Our destination was northwestern Connecticut, a refined enclave of smart little villages and towns with white clapperboard houses separated by miles and miles of wooded hills and lakes where black bears, coyotes and wild turkeys roam.

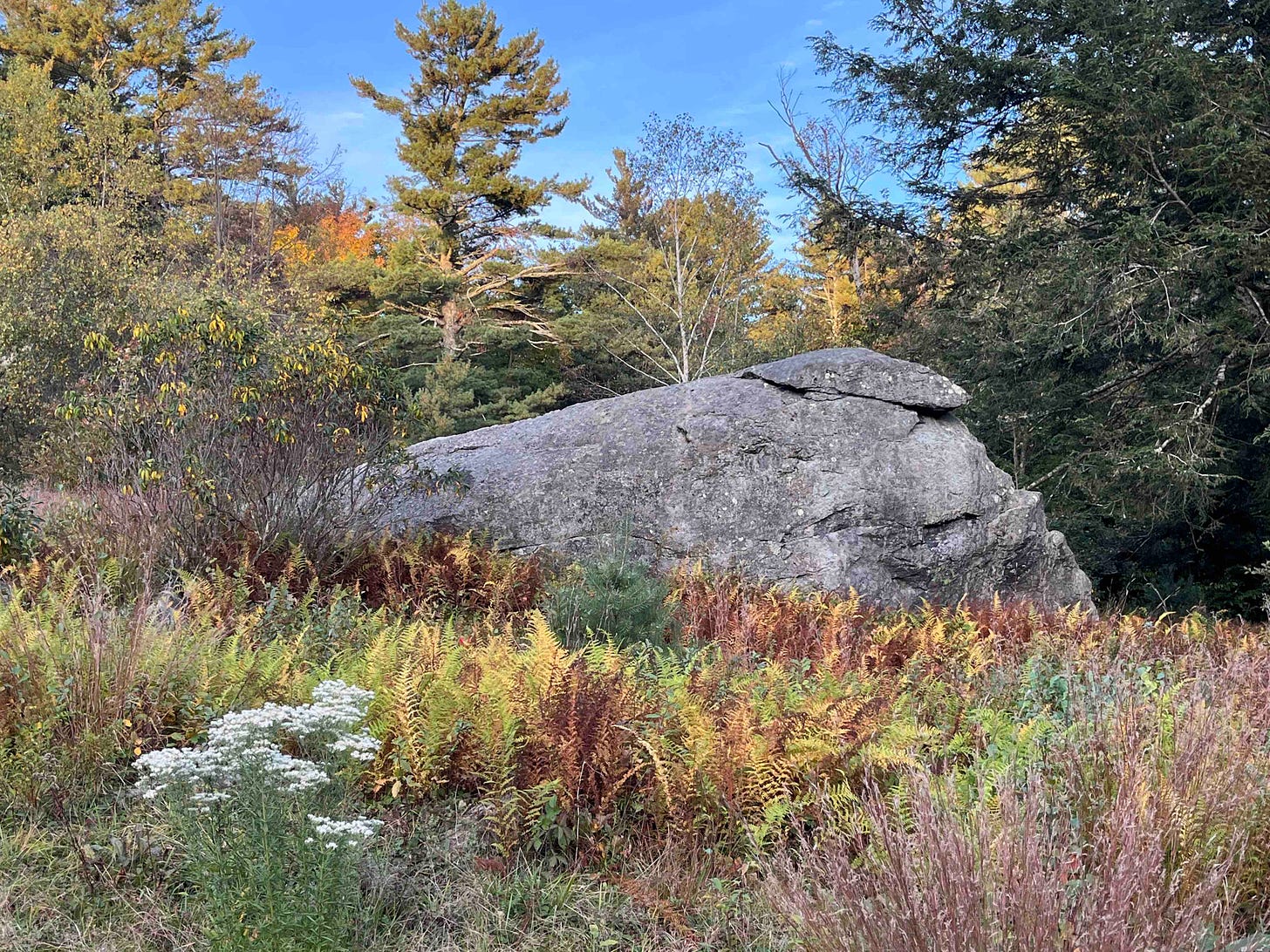

Near the village of Norfolk, Robin Hill is an elegant 1920s mansion with 20 acres of land which has been redesigned in the last 10 years by Dan Pearson. The owners liked the idea of keeping the garden very close to nature, and were introduced to Dan by their friend and neighbour John Paul Philippe. The result is the most extraordinary garden that flits between cultivated and natural. The huge sweep of native meadow that descends an incline at the front of the house takes your breath away, a fairytale clearing circled by trees, huge glacial boulders pushing up from the ground to give it a raw, elemental feel. In previous years the meadow was mown to oblivion, but now it has been returned to nature - yet it is never as simple as leaving a space to its own devices. Invasive plants have to be pulled out and plugs are added every year, gently encouraging the desirables while culling the thugs. As head gardener James McGrath says: ‘There is a constant dance between observation and action. Sometimes when people come round it’s really not obvious we have been gardening at all.’ Echinaceas, asters, eupatoriums and Sporobolus heterolepis are among the native plants encouraged here.

Dan removed a formal pergola in the orchard behind the house, preferring gently meandering mown paths leading to what is known as the cutting garden. Hidden behind a shimmering line of calamagrostis, the garden is as far away from a conventional cutting garden as you might imagine, with random drifts of flowers and foliage designed to feel like a pointillist painting. Late bees and butterflies were feeding on asters and calamintha, and birds balancing precariously on agastache seed heads.

The gentle gardening they are doing here is not confined to the open spaces. In the woods, too, subtle changes have been made, opening or concealing views, placing seats or benches as full stops, and encouraging a good ground flora. A conical stone cairn made by a local stonemason from stone dug out of the garden stands ghost-like in the woods, surrounded by ferns and a central ring of epimedium which makes it looks as if it is floating on a sea of green.

Both these gardens are indicative of the way garden design is heading at the moment, crossing and re-crossing the divide between gardened and wild, and throwing into question the very definition of what a garden can be. For the wider environment this trend can only be a positive thing.

Thank you, and it was indeed a great time to visit with the colours of the trees just turning. So enjoyed my trip!

Really inspiring Clare, and such a beautiful time to visit too.